Ricardo Bofill’s Walden 7 Turns 50

Landmark Social Housing Block Reaches a Half-Century in Great Shape

Walden 7 from the air, image courtesy of Ricardo Bofill Taller de Arquitectura

The Walden 7, a Fifty-Year-Old Watchtower in Sant Just Desvern

The Metropolitan Area of Barcelona is home to numerous architectural gems often ignored by visitors due to their location away from the center. However, in the town of Sant Just Desvern, west of Barcelona, there is a landmark that cannot go unnoticed by any passerby who gets there. It is the Walden 7, designed by Ricardo Bofill’s Taller de Arquitectura and inaugurated in 1975, no less than 50 years ago, an anniversary that Guiding Architects Barcelona wanted to highlight.

Walden 7 is a monumental social housing complex that marked an era and is clearly atypical, embodying a bold social and aesthetic utopia. At first glance it looks like a sort of reddish fortress, formed by the grouping of numerous blocks and perforated by huge voids that interconnect the communal spaces between them and with the outside.

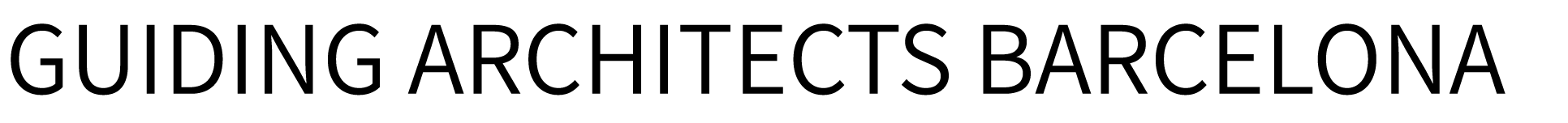

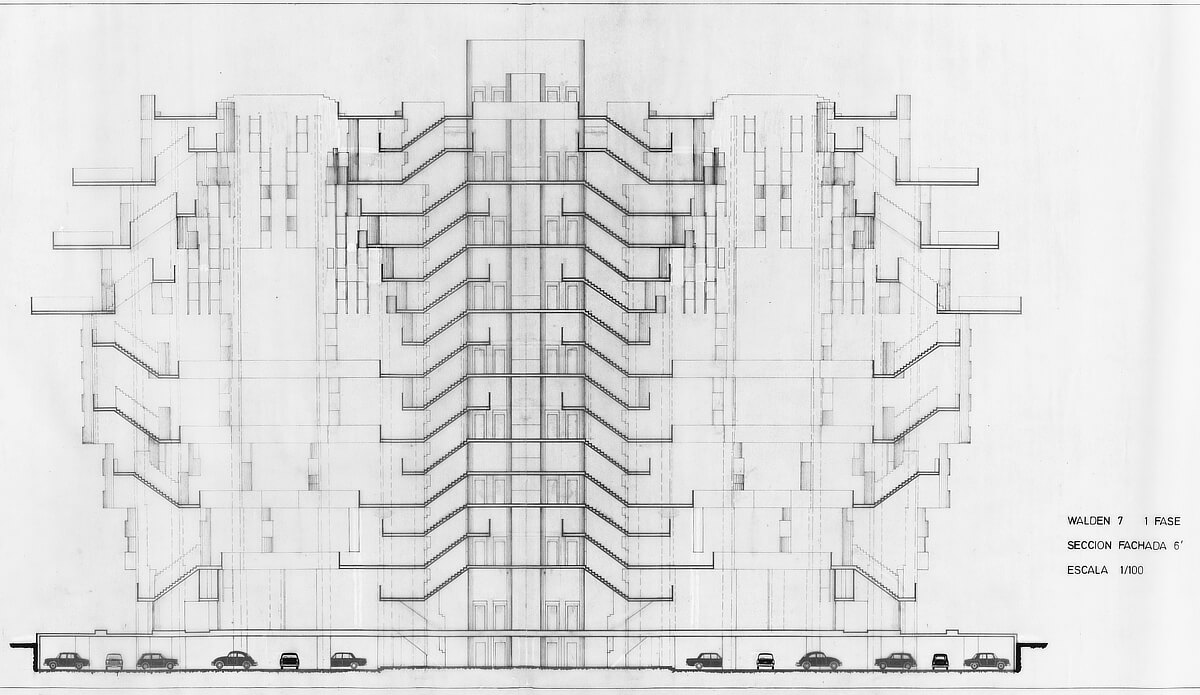

Walden 7 – longitudinal section, image courtesy of Ricardo Bofill Taller de Arquitectura

Catalan Counterculture in the Twilight of Franco’s Regime

Towards the end of the 1960’s Catalonia saw the rise of an anti-establishment effervescence that demanded liberties and positioned itself on the left of the political spectrum, but which seemed more focused on promoting alternative cultural expressions than on political confrontation with the Franco dictatorship. Thus arose the so-called gauche divine, a heterogeneous group of intellectuals ideologically influenced by May ’68, that included some prominent architects such as Oscar Tusquets, Oriol Bohigas and Ricardo Bofill.

The Emerging Trajectory of Ricardo Bofill in the 1960’s and 1970’s

Before designing the Walden 7 complex, Ricardo Bofill had already developed a remarkable career marked by formal experimentation and social aspirations. In 1963 he founded the Taller de Arquitectura in Barcelona, an interdisciplinary collective that included architects, urban planners, economists, artists and writers, with the aim of redefining architecture from a critical and more humanistic perspective.

Barrio Gaudí residential complex in Reus, image courtesy of Ricardo Bofill Taller de Arquitectura

In this first stage, Bofill developed a series of residential projects that tested new ways of living, such as the apartment building on Nicaragua Street in Barcelona (1964) or the Gaudí Neighborhood in Reus (1964-1970). These works have certain affinities with the ideas of the Grupo R and especially with the collective housing buildings of José Antonio Coderch, such as the apartments for the Urquijo Bank (1967-72) or the Cocheras de Sarrià building (1968), but they tried to go even further.

The approach combined the Mediterranean tradition and the prominence of brick with a formal experimentation based on complex geometric patterns and, in the case of the Reus estate, a renewed social concern for the collective use of community spaces.

Xanadu residential complex in Calpe

Xanadú and la Muralla Roja Continue the Transformation of Group Housing

Both Xanadú (1968-1971) and La Muralla Roja (1968-1973), located in Calp, Alicante, within walking distance of each other, represent a continuation of previous experiments in collective housing. And although both moved away from functionalist models, they seemed to do so in divergent directions.

In Xanadú, the Taller tested an assemblage composed of habitable capsules arranged around vertical cores, resulting in an allegorical volume that recalled Japanese castles. Its expression, however, was based on vernacular elements such as shutters and tiles, and seemed to announce an approach to postmodernist formulas.

La Muralla Roja (the Red Wall), on the other hand, presented an orthogonal volumetry based on modules grouped around courtyards, creating common spaces and paths of great formal complexity. Its language was perceived as more abstract, partly because of the vibrant chromatic proposal, but it was inspired by the kasbahs of Algeria or Morocco.

La Muralla Roja residential complex in Calpe, © Ana Hidalgo Burgos

The City in Space, the Direct Precedent of Walden 7

Walden 7 is a reduced and somewhat less ambitious version of The City in Space, a large-scale housing proposal with a markedly utopian and perhaps somewhat megalomaniacal premise that the Taller de Arquitectura attempted to carry out in Madrid in 1970. The project aimed at creating a multifunctional complex, including commerce and services, structured by interconnected collective spaces that would foster an enhanced sense of community.

The starting point at the formal level was again a three-dimensional grid that sought to establish an underlying order based on “organic” and highly complex configurations. Flexibility was an additional intent in the approach to both community spaces and dwellings, so that they could adapt to the evolving needs of the users.

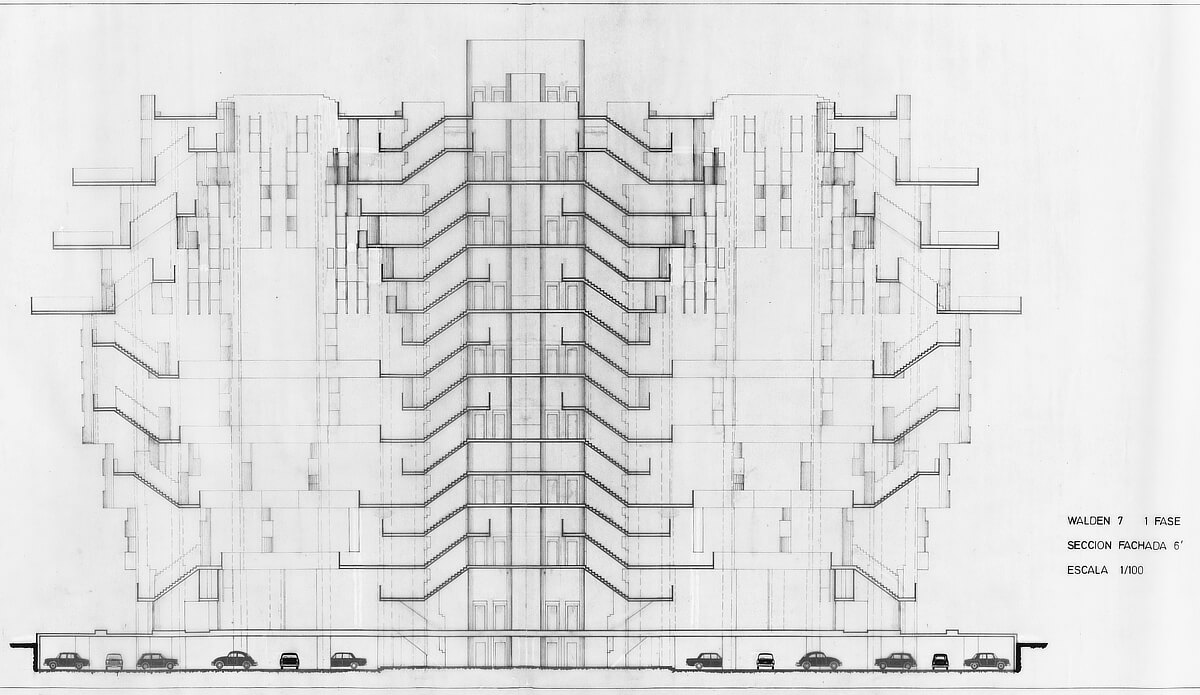

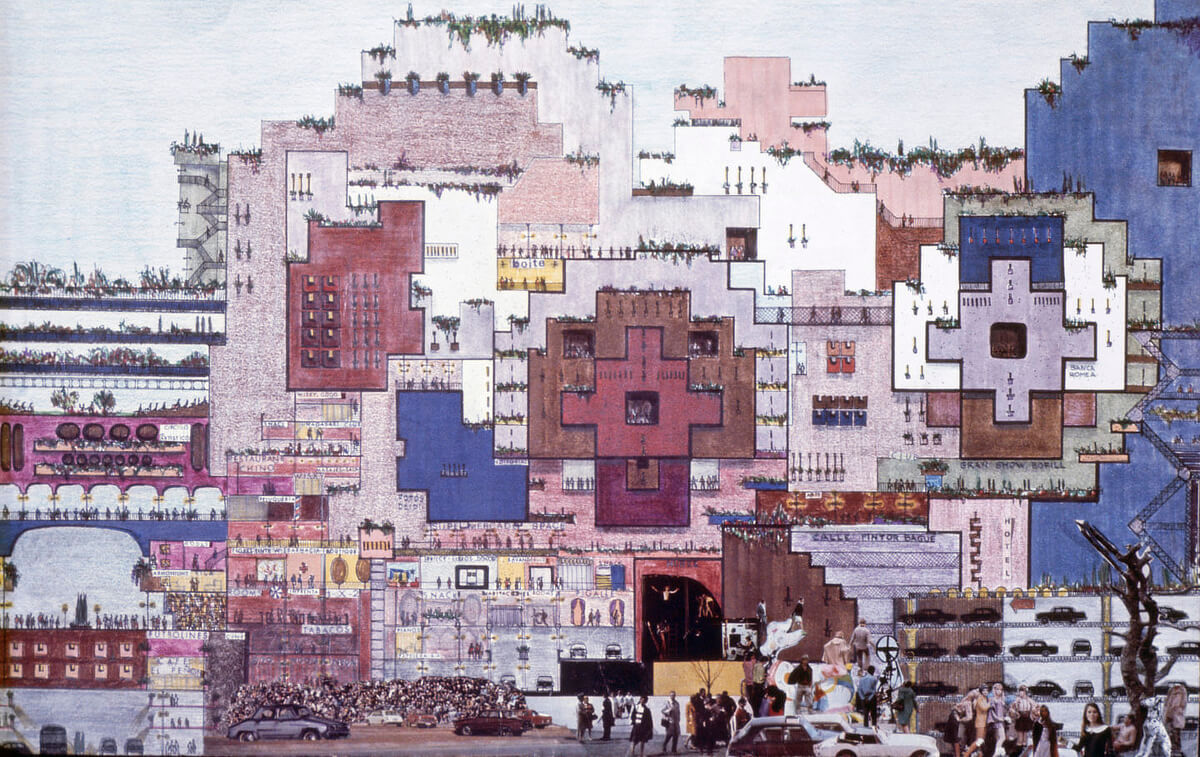

The City in Space residential project, image courtesy of Ricardo Bofill Taller de Arquitectura

It is also interesting to note that the images produced by the team for the City in Space were immersed in a Pop aesthetic resembling that displayed in projects by Archigram and featured in 1960’s popular culture icons such as The Beatles’ film “Yellow Submarine”. Unfortunately, The City in Space ran into all kinds of adversity, starting with the reluctance of the authorities and the construction company, which ended up stopping the project.

The Housing Utopia Crystallizes in Barcelona

The opportunity arose in 1972 to apply many of the ideas and solutions elaborated for The City in Space in a new megaproject, this time located in the outskirts of Barcelona. In its initial version, it was a low-budget social housing complex conceived as a “vertical neighborhood” that occupied a complete block, with two additional buildings similar to the one completed. It therefore coincided with Oriol Bohigas’ desire to “monumentalize the periphery” of Barcelona, providing it with large-scale buildings with a strong symbolic significance.

Walden 7 under construction, image courtesy of Ricardo Bofill Taller de Arquitectura

The Taller de Arquitectura chose the name Walden 7 for the project, based on the science fiction novel “Walden 2” by B. F. Skinner (1948), which narrates the visit of a scientist to a utopian community in which the built environment conditioned the behavior of the citizens. The novel in turn had taken its name from Henry David Thoreau’s celebrated “Walden” (1854), an autobiographical and transcendental testimony about the two years the author spent in a self-built cabin in a Massachusetts forest.

The framework of these two literary pieces evidences the aspirations of Bofill and his team.

Towards Modular, Vertical and Flexible Collective Housing

Although the idea of a modular vertical city had precedents in the trajectory of the Taller de Arquitectura itself, it is important to mention that it was also inspired by utopian proposals from other countries, such as the Plug-in City (1964) by the British group Archigram or architectural and urbanistic projects by the Japanese Metabolists. Both groups proposed systems based on modular megastructures in which prefabricated constructive pieces fit together like capsules, clearly differentiated from the structure.

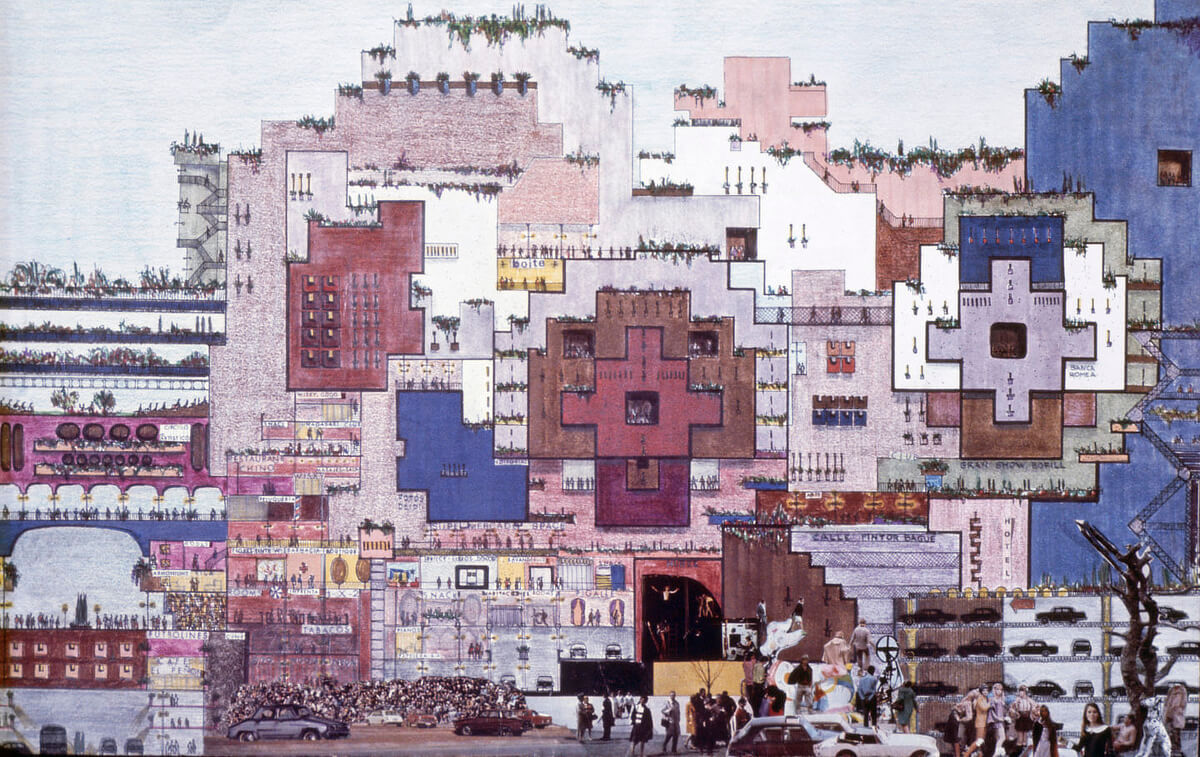

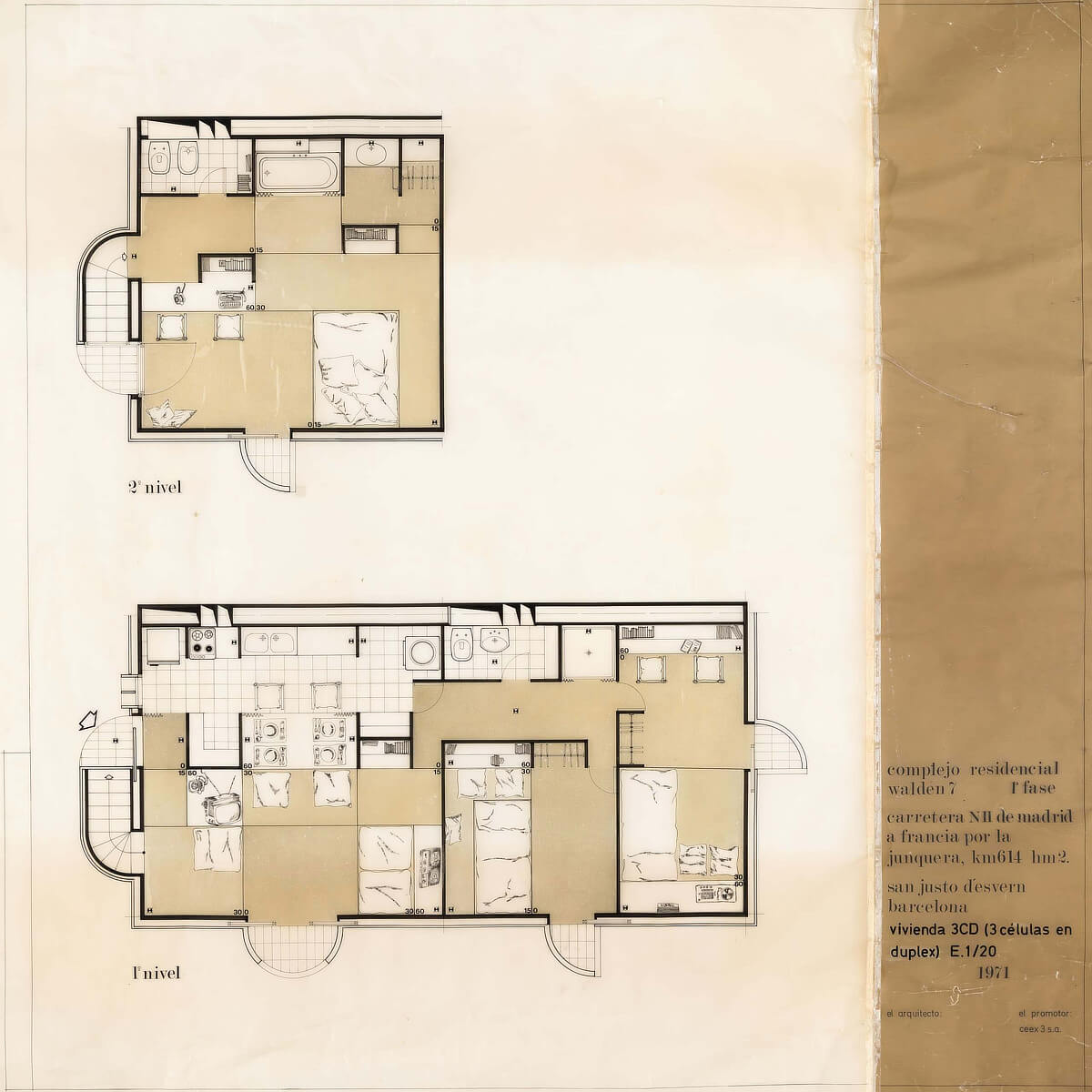

Walden 7 – maisonette apartment, image courtesy of Ricardo Bofill Taller de Arquitectura

Bofill and his team opted instead to work with a more conceptual than structural modulation, which resulted in a more conventional construction process, but also in a more unitary reading of the building, ultimately contributing to the economic viability of the project.

Therefore, concrete ended up being the predominant material and was used for both the structure and the prefabricated enclosure blocks. The ceramic components in orange ochre on the exterior and shades of blue on the interior, which played an important role in reinforcing the Mediterranean character of the project, were used only as cladding.

On a formal and functional level, the 30 m2 square modules were grouped in an array of configurations, creating one- or two-level apartments of different sizes. The system was clearly intended as a flexible solution to facilitate changes in the medium and long term.

Walden 7 – inner courtyard, © Roc Isern, licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

Rediscovering the Living Space: Sensory Itineraries and Community

Spatially, Walden 7 is a box of surprises: the geometric modules seem to have exploded under the effect of an invisible centrifugal force, leaving two large, staggered voids, flanked by galleries and crossed by bridges at different levels. In these overwhelming yet slightly labyrinthine spaces, the imaginary prisons of Giovanni Battista Piranesi resound.

As you walk through and around them, there are contrasts of light, color and space, and as you walk through the semi-public areas, you suddenly see new perspectives, perhaps of the same multi-height space that you saw a few moments ago, fragmented into countless terraces and corridors that encourage interaction among the neighbors.

Numerous evidence shows how users enjoy and appropriate every corner of the community space. There are all kinds of flowerpots, doormats, bicycles, clotheslines and even a two-seater sofa, installed on a terrace that acquires a certain intimate character.

Walden 7 – corridors, bridges and balconies inside the building, © Till F. Teenck, licensed under CC BY-SA 2.5

Echoes of the Past and Contemporary Resonances in Walden 7

While officially the Taller de Arquitectura mentioned Algerian kasbahs as a source of inspiration, it seems evident that the references for this housing complex are numerous. In addition to some mentioned above, looking into the more distant past, Walden 7 can be read as a reinterpretation of the Mesopotamian ziggurat. A staggered Tower of Babel stacked on top of an inverted one, clad in ceramic tiles.

Christian Norberg-Schulz, on the other hand, pointed out the complex and contradictory character of the building, linking it to the theoretical premises of Robert Venturi, but also to Baroque architecture, in which intermediate spaces, lighting contrasts, double envelopes and dynamic spatial effects are equally protagonists.

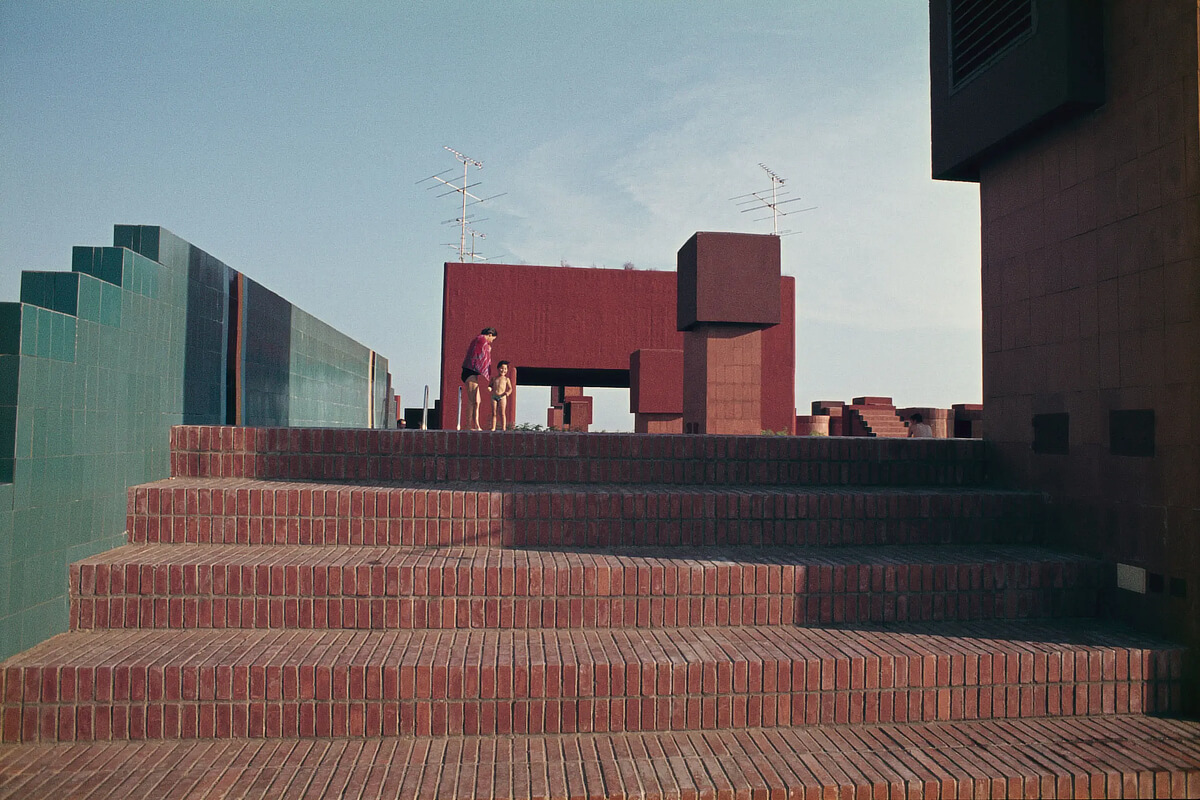

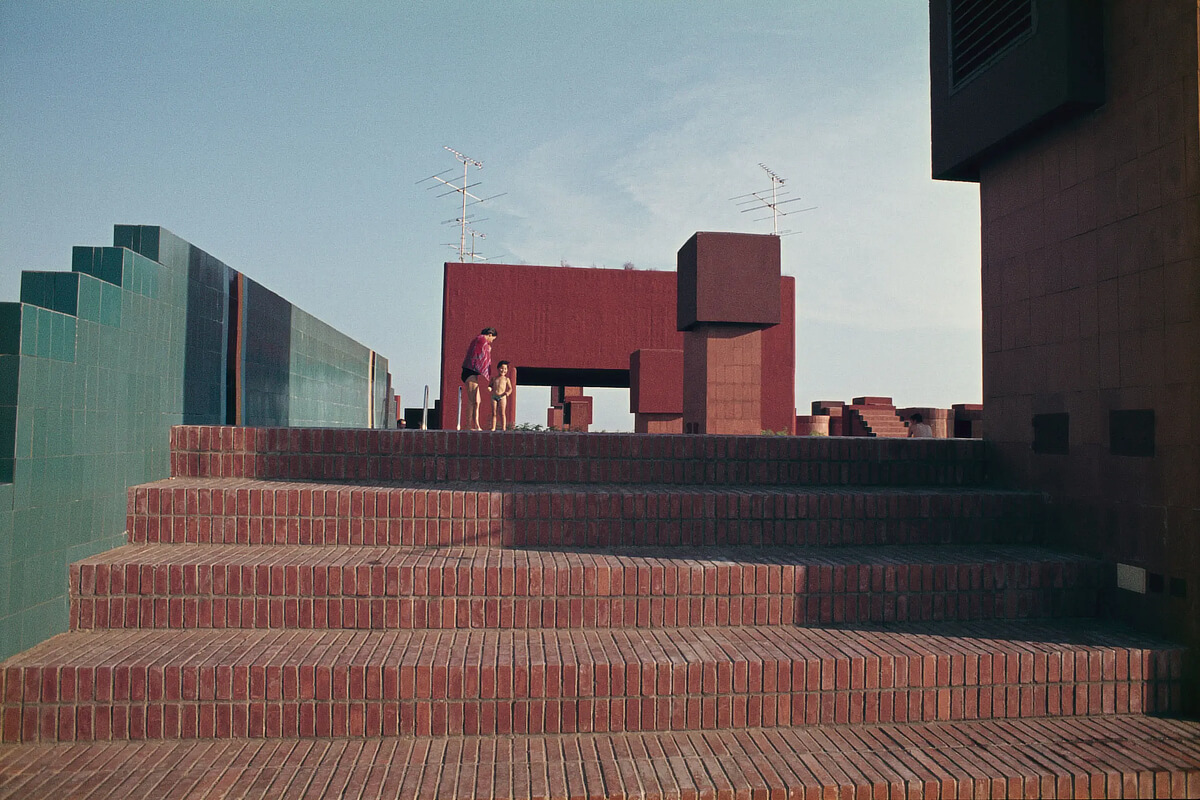

Walden 7 – roof terrace, image courtesy of Ricardo Bofill Taller de Arquitectura

And returning to the twentieth century, both for its monumentality of medieval reminiscences, as for its grouped volumetric configuration or for its elaborate articulating spaces, the building seems to be in tune with the architecture of master Louis Kahn. To these features we can add the harmonious coexistence of the human scale with the monumental scale, embodied in the combination of the apartment windows and the openings of the ensemble, that recall specific buildings of Kahn such as the Parliament of Dhaka (1964-82).

The Resilience of an Enduring Architectural Icon

Despite the many difficulties encountered by Walden 7 over the years, the building retains its seductive power intact. The confrontations with the developer, the need for a special foundation due to the low resistance of the soil, the complaints of some neighbors and certain construction deficiencies, noticeably the inconvenient detachment of the original cladding only a year after the building was completed, led Bofill himself to express a certain disenchantment with the result.

Walden 7 – original and architectural model, image courtesy of Ricardo Bofill Taller de Arquitectura

However, all these challenges can now be seen as overcome obstacles. In the 1993 renovation, for example, the ceramic tiles were replaced with a coating of plaster, which allowed a new layer of thermal insulation to be added and improved living conditions.

If anyone today doubts the value of this emblematic building, or its spatial and social qualities, a visit to it should be enough to dispel them completely. The enduring validity of Walden 7, fifty years after its completion, can also be seen in its influence on various housing projects of the 21st century, such as the Mirador Building in Madrid (2005) by MVRDV, the 79&Park building in Stockholm by Bjarke Ingels (2018) or recent social housing buildings in Barcelona itself.

Walden 7, © Roc Isern, licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

Text: Pedro Capriata

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Álvarez, R., Galvan-Desvaux, N. Martínez J. M. (2024). Building the Walden 7. The Model as Patrimony of the Design Process. In L. Agustín-Hernández, A. Vallespín, A. Fernández-Morales (Eds.), Graphical Heritage, Vol. 2 -Representation, Analysis, Concept and Creation (pp 108-117). Springer.

Benevolo, L. (1994). Historia de la Arquitectura Moderna. Gustavo Gili.

Bofill, A. (1975). Contribución al estudio de la generación geométrica de formas arquitectónicas y urbanas. Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya.

Bofill, R. (1978). L’Architecture d’un Homme. Arthaud.

Bofill, R. (1989). Espaces d’une vie. Odile Jacob.

Bofill, R. (2009). Architecture in the Era of Local Culture and International Experience. Ricardo Bofill Taller de Arquitectura.

Capitel, A. (2023). Arquitecturas españolas en el siglo XX. Abada Editores.

Centre Obert d’Arquitectura (s.f.) ArquitecturaCatalana.Cat.

https://www.arquitecturacatalana.cat/es

Cruells, B. (1998). Ricardo Bofill. Gustavo Gili.

D’Huart, A. (Ed.) (1984). Ricardo Bofill: taller de arquitectura. El dibujo de la ciudad. Industria y clasicismo. Gustavo Gili.

Frampton, K. (1992). Modern Architecture. A Critical History. Thames and Hudson.

Futagawa, Y., Norberg-Schulz, C. (1985). Ricardo Bofill: Taller de Arquitectura. A.D.A. Edita Tokyo.

Klanten, R., Niebius, M. E., Marinai, V. (Ed.) (2019). Ricardo Bofill. Visions of Architecture. Gestalten.

Montaner, J.M. (2005). Arquitectura contemporània a Catalunya. Edicions 62.

Pla, M. (2007). Catalunya. Guia d’arquitectura moderna 1880-2007. Triangle.

Solé, J. L., Amigó J. (1995). Walden 7 i mig. Ajuntament de Sant Just Desvern.

Urrutia, A. (2003). Arquitectura española, siglo XX. Cátedra.

Warren, J. A. (Ed.) (1988). Ricardo Bofill. Taller de Arquitectura: Buildings and Projects, 1960-85. Rizzoli.

Ricardo Bofill’s Walden 7 Turns 50

Landmark Social Housing Block Reaches a Half-Century in Great Shape

Walden 7 from the air, image courtesy of Ricardo Bofill Taller de Arquitectura

The Walden 7, a Fifty-Year-Old Watchtower in Sant Just Desvern

The Metropolitan Area of Barcelona is home to numerous architectural gems often ignored by visitors due to their location away from the center. However, in the town of Sant Just Desvern, west of Barcelona, there is a landmark that cannot go unnoticed by any passerby who gets there. It is the Walden 7, designed by Ricardo Bofill’s Taller de Arquitectura and inaugurated in 1975, no less than 50 years ago, an anniversary that Guiding Architects Barcelona wanted to highlight.

Walden 7 is a monumental social housing complex that marked an era and is clearly atypical, embodying a bold social and aesthetic utopia. At first glance it looks like a sort of reddish fortress, formed by the grouping of numerous blocks and perforated by huge voids that interconnect the communal spaces between them and with the outside.

Walden 7 – longitudinal section, image courtesy of Ricardo Bofill Taller de Arquitectura

Catalan Counterculture in the Twilight of Franco’s Regime

Towards the end of the 1960’s Catalonia saw the rise of an anti-establishment effervescence that demanded liberties and positioned itself on the left of the political spectrum, but which seemed more focused on promoting alternative cultural expressions than on political confrontation with the Franco dictatorship. Thus arose the so-called gauche divine, a heterogeneous group of intellectuals ideologically influenced by May ’68, that included some prominent architects such as Oscar Tusquets, Oriol Bohigas and Ricardo Bofill.

The Emerging Trajectory of Ricardo Bofill in the 1960’s and 1970’s

Before designing the Walden 7 complex, Ricardo Bofill had already developed a remarkable career marked by formal experimentation and social aspirations. In 1963 he founded the Taller de Arquitectura in Barcelona, an interdisciplinary collective that included architects, urban planners, economists, artists and writers, with the aim of redefining architecture from a critical and more humanistic perspective.

Barrio Gaudí residential complex in Reus, image courtesy of Ricardo Bofill Taller de Arquitectura

In this first stage, Bofill developed a series of residential projects that tested new ways of living, such as the apartment building on Nicaragua Street in Barcelona (1964) or the Gaudí Neighborhood in Reus (1964-1970). These works have certain affinities with the ideas of the Grupo R and especially with the collective housing buildings of José Antonio Coderch, such as the apartments for the Urquijo Bank (1967-72) or the Cocheras de Sarrià building (1968), but they tried to go even further.

The approach combined the Mediterranean tradition and the prominence of brick with a formal experimentation based on complex geometric patterns and, in the case of the Reus estate, a renewed social concern for the collective use of community spaces.

Xanadu residential complex in Calpe

Xanadú and la Muralla Roja Continue the Transformation of Group Housing

Both Xanadú (1968-1971) and La Muralla Roja (1968-1973), located in Calp, Alicante, within walking distance of each other, represent a continuation of previous experiments in collective housing. And although both moved away from functionalist models, they seemed to do so in divergent directions.

In Xanadú, the Taller tested an assemblage composed of habitable capsules arranged around vertical cores, resulting in an allegorical volume that recalled Japanese castles. Its expression, however, was based on vernacular elements such as shutters and tiles, and seemed to announce an approach to postmodernist formulas.

La Muralla Roja (the Red Wall), on the other hand, presented an orthogonal volumetry based on modules grouped around courtyards, creating common spaces and paths of great formal complexity. Its language was perceived as more abstract, partly because of the vibrant chromatic proposal, but it was inspired by the kasbahs of Algeria or Morocco.

La Muralla Roja residential complex in Calpe, © Ana Hidalgo Burgos

The City in Space, the Direct Precedent of Walden 7

Walden 7 is a reduced and somewhat less ambitious version of The City in Space, a large-scale housing proposal with a markedly utopian and perhaps somewhat megalomaniacal premise that the Taller de Arquitectura attempted to carry out in Madrid in 1970. The project aimed at creating a multifunctional complex, including commerce and services, structured by interconnected collective spaces that would foster an enhanced sense of community.

The starting point at the formal level was again a three-dimensional grid that sought to establish an underlying order based on “organic” and highly complex configurations. Flexibility was an additional intent in the approach to both community spaces and dwellings, so that they could adapt to the evolving needs of the users.

The City in Space residential project, image courtesy of Ricardo Bofill Taller de Arquitectura

It is also interesting to note that the images produced by the team for the City in Space were immersed in a Pop aesthetic resembling that displayed in projects by Archigram and featured in 1960’s popular culture icons such as The Beatles’ film “Yellow Submarine”. Unfortunately, The City in Space ran into all kinds of adversity, starting with the reluctance of the authorities and the construction company, which ended up stopping the project.

The Housing Utopia Crystallizes in Barcelona

The opportunity arose in 1972 to apply many of the ideas and solutions elaborated for The City in Space in a new megaproject, this time located in the outskirts of Barcelona. In its initial version, it was a low-budget social housing complex conceived as a “vertical neighborhood” that occupied a complete block, with two additional buildings similar to the one completed. It therefore coincided with Oriol Bohigas’ desire to “monumentalize the periphery” of Barcelona, providing it with large-scale buildings with a strong symbolic significance.

Walden 7 under construction, image courtesy of Ricardo Bofill Taller de Arquitectura

The Taller de Arquitectura chose the name Walden 7 for the project, based on the science fiction novel “Walden 2” by B. F. Skinner (1948), which narrates the visit of a scientist to a utopian community in which the built environment conditioned the behavior of the citizens. The novel in turn had taken its name from Henry David Thoreau’s celebrated “Walden” (1854), an autobiographical and transcendental testimony about the two years the author spent in a self-built cabin in a Massachusetts forest.

The framework of these two literary pieces evidences the aspirations of Bofill and his team.

Towards Modular, Vertical and Flexible Collective Housing

Although the idea of a modular vertical city had precedents in the trajectory of the Taller de Arquitectura itself, it is important to mention that it was also inspired by utopian proposals from other countries, such as the Plug-in City (1964) by the British group Archigram or architectural and urbanistic projects by the Japanese Metabolists. Both groups proposed systems based on modular megastructures in which prefabricated constructive pieces fit together like capsules, clearly differentiated from the structure.

Walden 7 – maisonette apartment, image courtesy of Ricardo Bofill Taller de Arquitectura

Bofill and his team opted instead to work with a more conceptual than structural modulation, which resulted in a more conventional construction process, but also in a more unitary reading of the building, ultimately contributing to the economic viability of the project.

Therefore, concrete ended up being the predominant material and was used for both the structure and the prefabricated enclosure blocks. The ceramic components in orange ochre on the exterior and shades of blue on the interior, which played an important role in reinforcing the Mediterranean character of the project, were used only as cladding.

On a formal and functional level, the 30 m2 square modules were grouped in an array of configurations, creating one- or two-level apartments of different sizes. The system was clearly intended as a flexible solution to facilitate changes in the medium and long term.

Walden 7 – inner courtyard, © Roc Isern, licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

Rediscovering the Living Space: Sensory Itineraries and Community

Spatially, Walden 7 is a box of surprises: the geometric modules seem to have exploded under the effect of an invisible centrifugal force, leaving two large, staggered voids, flanked by galleries and crossed by bridges at different levels. In these overwhelming yet slightly labyrinthine spaces, the imaginary prisons of Giovanni Battista Piranesi resound.

As you walk through and around them, there are contrasts of light, color and space, and as you walk through the semi-public areas, you suddenly see new perspectives, perhaps of the same multi-height space that you saw a few moments ago, fragmented into countless terraces and corridors that encourage interaction among the neighbors.

Numerous evidence shows how users enjoy and appropriate every corner of the community space. There are all kinds of flowerpots, doormats, bicycles, clotheslines and even a two-seater sofa, installed on a terrace that acquires a certain intimate character.

Walden 7 – corridors, bridges and balconies inside the building, © Till F. Teenck, licensed under CC BY-SA 2.5

Echoes of the Past and Contemporary Resonances in Walden 7

While officially the Taller de Arquitectura mentioned Algerian kasbahs as a source of inspiration, it seems evident that the references for this housing complex are numerous. In addition to some mentioned above, looking into the more distant past, Walden 7 can be read as a reinterpretation of the Mesopotamian ziggurat. A staggered Tower of Babel stacked on top of an inverted one, clad in ceramic tiles.

Christian Norberg-Schulz, on the other hand, pointed out the complex and contradictory character of the building, linking it to the theoretical premises of Robert Venturi, but also to Baroque architecture, in which intermediate spaces, lighting contrasts, double envelopes and dynamic spatial effects are equally protagonists.

Walden 7 – roof terrace, image courtesy of Ricardo Bofill Taller de Arquitectura

And returning to the twentieth century, both for its monumentality of medieval reminiscences, as for its grouped volumetric configuration or for its elaborate articulating spaces, the building seems to be in tune with the architecture of master Louis Kahn. To these features we can add the harmonious coexistence of the human scale with the monumental scale, embodied in the combination of the apartment windows and the openings of the ensemble, that recall specific buildings of Kahn such as the Parliament of Dhaka (1964-82).

The Resilience of an Enduring Architectural Icon

Despite the many difficulties encountered by Walden 7 over the years, the building retains its seductive power intact. The confrontations with the developer, the need for a special foundation due to the low resistance of the soil, the complaints of some neighbors and certain construction deficiencies, noticeably the inconvenient detachment of the original cladding only a year after the building was completed, led Bofill himself to express a certain disenchantment with the result.

Walden 7 – original and architectural model, image courtesy of Ricardo Bofill Taller de Arquitectura

However, all these challenges can now be seen as overcome obstacles. In the 1993 renovation, for example, the ceramic tiles were replaced with a coating of plaster, which allowed a new layer of thermal insulation to be added and improved living conditions.

If anyone today doubts the value of this emblematic building, or its spatial and social qualities, a visit to it should be enough to dispel them completely. The enduring validity of Walden 7, fifty years after its completion, can also be seen in its influence on various housing projects of the 21st century, such as the Mirador Building in Madrid (2005) by MVRDV, the 79&Park building in Stockholm by Bjarke Ingels (2018) or recent social housing buildings in Barcelona itself.

Walden 7, © Roc Isern, licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

Text: Pedro Capriata

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Álvarez, R., Galvan-Desvaux, N. Martínez J. M. (2024). Building the Walden 7. The Model as Patrimony of the Design Process. In L. Agustín-Hernández, A. Vallespín, A. Fernández-Morales (Eds.), Graphical Heritage, Vol. 2 -Representation, Analysis, Concept and Creation (pp 108-117). Springer.

Benevolo, L. (1994). Historia de la Arquitectura Moderna. Gustavo Gili.

Bofill, A. (1975). Contribución al estudio de la generación geométrica de formas arquitectónicas y urbanas. Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya.

Bofill, R. (1978). L’Architecture d’un Homme. Arthaud.

Bofill, R. (1989). Espaces d’une vie. Odile Jacob.

Bofill, R. (2009). Architecture in the Era of Local Culture and International Experience. Ricardo Bofill Taller de Arquitectura.

Capitel, A. (2023). Arquitecturas españolas en el siglo XX. Abada Editores.

Centre Obert d’Arquitectura (s.f.) ArquitecturaCatalana.Cat.

https://www.arquitecturacatalana.cat/es

Cruells, B. (1998). Ricardo Bofill. Gustavo Gili.

D’Huart, A. (Ed.) (1984). Ricardo Bofill: taller de arquitectura. El dibujo de la ciudad. Industria y clasicismo. Gustavo Gili.

Frampton, K. (1992). Modern Architecture. A Critical History. Thames and Hudson.

Futagawa, Y., Norberg-Schulz, C. (1985). Ricardo Bofill: Taller de Arquitectura. A.D.A. Edita Tokyo.

Klanten, R., Niebius, M. E., Marinai, V. (Ed.) (2019). Ricardo Bofill. Visions of Architecture. Gestalten.

Montaner, J.M. (2005). Arquitectura contemporània a Catalunya. Edicions 62.

Pla, M. (2007). Catalunya. Guia d’arquitectura moderna 1880-2007. Triangle.

Solé, J. L., Amigó J. (1995). Walden 7 i mig. Ajuntament de Sant Just Desvern.

Urrutia, A. (2003). Arquitectura española, siglo XX. Cátedra.

Warren, J. A. (Ed.) (1988). Ricardo Bofill. Taller de Arquitectura: Buildings and Projects, 1960-85. Rizzoli.

Related Posts

16.02.2026

Barcelona, World Capital of Architecture, Kicks off a Unique Year – And We Invite You to Experience the City With Us.

19.01.2026

Exhibitions, Academic Events, Projections and Concerts Will Fill Barcelona to Commemorate the Centenary of Antoni Gaudí’s Death.

15.12.2025

An Invitation to (Re)Discover the City and Its Architecture as the Main Protagonist.

17.11.2025

Barcelona’s Historic Promontory Reinvents Itself as the Fira Gears up for the 1929 International Exhibition’s Centenary.