Barcelona’s Superblocks and Green Axes, a Pathway Towards a More Sustainable City

The City Accelerates the Process of Urban Regeneration With the Incorporation of Green Axes and Squares.

Sant Antoni Superblock, © Mariona Gil/barcelona.cat, licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

Superblocks: Reinventing Barcelona’s Public Spaces

One of the most stimulating urban proposals of the last decades can be found, once again, in the prolific Barcelona. We are talking about the Superblocks or Superilles, an approach that goes beyond the implications of its name and encompasses a comprehensive renovation project for the city. As expected, the first superblocks implemented have focused the debate on the potential qualities and drawbacks of the concept. Barcelona’s City Council presented them as pilot tests, but also as an inevitable change of model that would ensure the sustainability of the city in the medium and long term. Perhaps this is where the communication problems begin because it is as if we were being told “try this and see if you like it… but if you don’t, you’ll have to eat it anyway”.

But let’s start by defining what superblocks are. In the most elementary sense, they are mega-blocks made up of the union of nine pre-existing blocks. The merger is obviously not achieved by filling the spaces between blocks with buildings, but by transforming the public space between them. Changes include new uses and restriction of car access in favor of pedestrians and bicycles. The objectives include reducing noise, traffic and pollution within these areas, providing citizens with more and better living spaces, and overall, making Barcelona a more sustainable city.

Playground within the Poblenou Superblock, © Curro Palacios/barcelona.cat, licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

While in theory this method would be applicable in any city with a regular layout, it is particularly interesting in the context of the Eixample, the Barcelona expansion project devised by Ildefons Cerdà in the mid-19th century. The Cerdà Plan was not followed to the letter, but the grid layout, the proposed street widths and the characteristic chamfers at the corners of the blocks were almost always respected. These chamfers are what now enable the creation of public squares of different character at the pedestrianized intersections.

Revitalizing the Streets: Salvador Rueda and the Legacy of Jane Jacobs

Let us now try to explore the origin of this concept. The driving force behind this proposal is Salvador Rueda, a psychologist specializing in urban planning and sustainability issues with an extended career in public institutions. While Rueda’s specific approaches are novel, they are based on principles that have been at the center of the urban planning debate for decades and that revolve mainly around the prioritization of pedestrian space.

It would therefore make sense to look for precedents in the ideas of Jane Jacobs, a seminal figure in the emergence and consolidation of current urban theories. Jacobs (2011) put people at the center of her plan, analyzed existing situations and proposed strategies such as functional diversification to improve and revitalize urban environments.

Pavement markings at Carrer Pelai, © Ajuntament de Barcelona, licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

In one of the premises of The Death and Life of Great American Cities, Jacobs recommended reducing the size of city blocks. At first we might think that Rueda is moving in the opposite direction of the author, but if we read Jacobs’ explanation carefully, we will see that this is not the case. The objective of reducing blocks was to increase and diversify pedestrian flows, something that the superblocks achieve, at least in part.

Jacobs’ only objection that might be relevant in this context would be that large blocks make access to public transportation more difficult. But if these were to magically split as her diagrams suggest, it is unlikely that public transport would alter its established routes. It would seem then that the superblocks follow Jacobs’ theoretical framework in most of their guidelines.

Slowing Down Flows and Blurring Boundaries: Jahn Gehl and the “Soft Edges”

In the superblocks we can also glimpse at concepts proposed by the Dane Jan Gehl, another of the great references of contemporary urbanism. Gehl has played a crucial role in the pedestrianization of Copenhagen, but above all he has exerted an enormous influence through his texts. Among his guiding ideas is one that is also central for Rueda: reducing traffic speeds. In the superblock prototypes in Barcelona, not only has car access been restricted, but the speed limits applied might seem excessively rigorous (10 km/h).

Running track within the Poblenou Superblock, © Curro Palacios/barcelona.cat, licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

Another of Gehl’s (2006) premises that we see partially applied are the so called “soft edges”, which may consist of permeable facades with social or commercial activity, or alternatively a succession of in-between spaces that blur the boundaries between public and private. In these cases, vegetation should play a decisive role. It is foreseeable that the conditions of each environment will determine the type of soft edges to be applied and therefore the results may vary.

In the Sant Antoni Superblock we see a more stimulating environment due to the continuity of the facades and the presence of stores. In Poblenou, on the other hand, with discontinuous volumes, the interaction between public and private seems to depend more on in-between spaces. The concept of soft edges is perfectly in tune with the objectives of the superblocks and should perhaps be incorporated more consistently into the debate regarding the future of the urban plan. In what ways could the interaction between buildings and the street be improved?

Sant Antoni Superblock, © Mariona Gil/barcelona.cat, licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

It is timely to recall a final theme that shapes Gehl’s theories: his warning about lengthy paths and oversized spaces. From this perspective, the superblocks perhaps start with a disadvantage: in Cerdà’s Eixample the large dimensions of the grid are a binding framework and indeed in certain cases the pedestrianized areas may seem excessive or underutilized. But precisely for this reason it is essential to be aware that in order to transform public space it is not only necessary to create places for citizens and encourage mixed activities: it is equally important to maintain accurate scales through the fragmentation of paths and spaces.

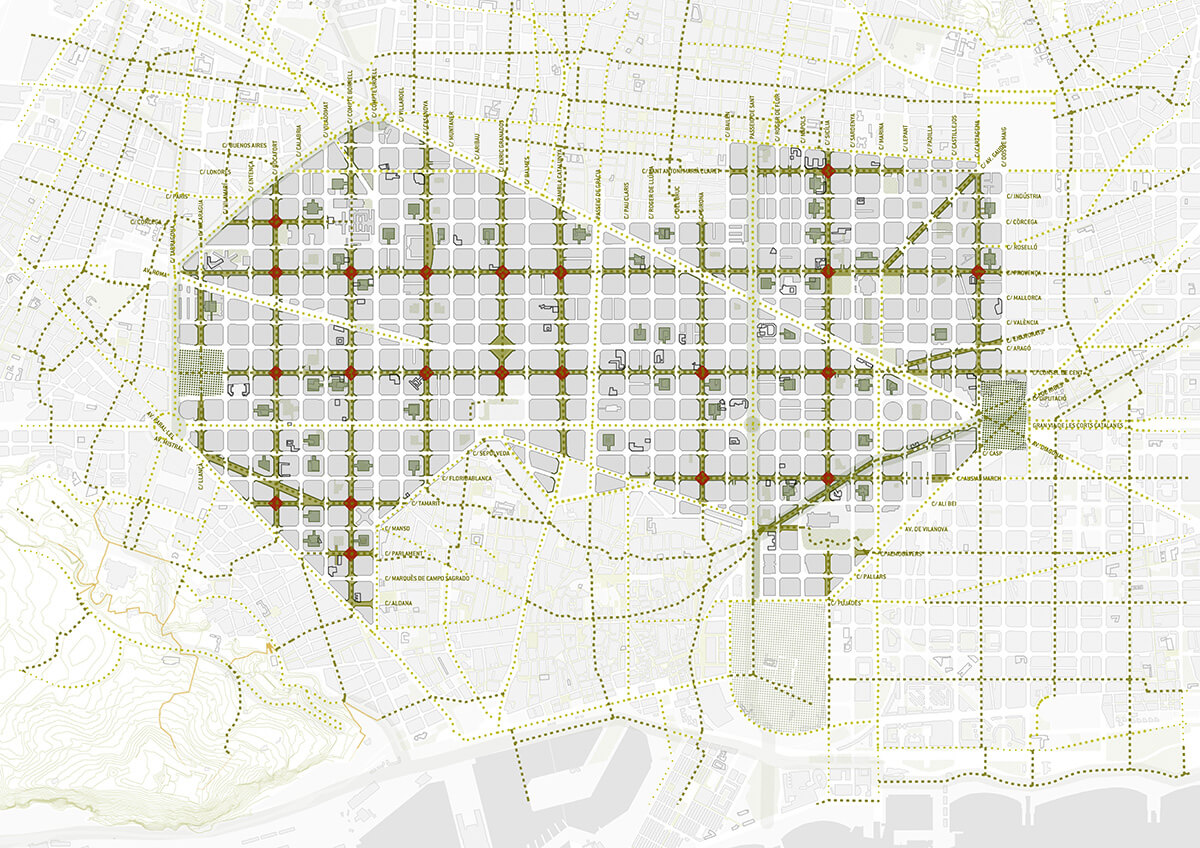

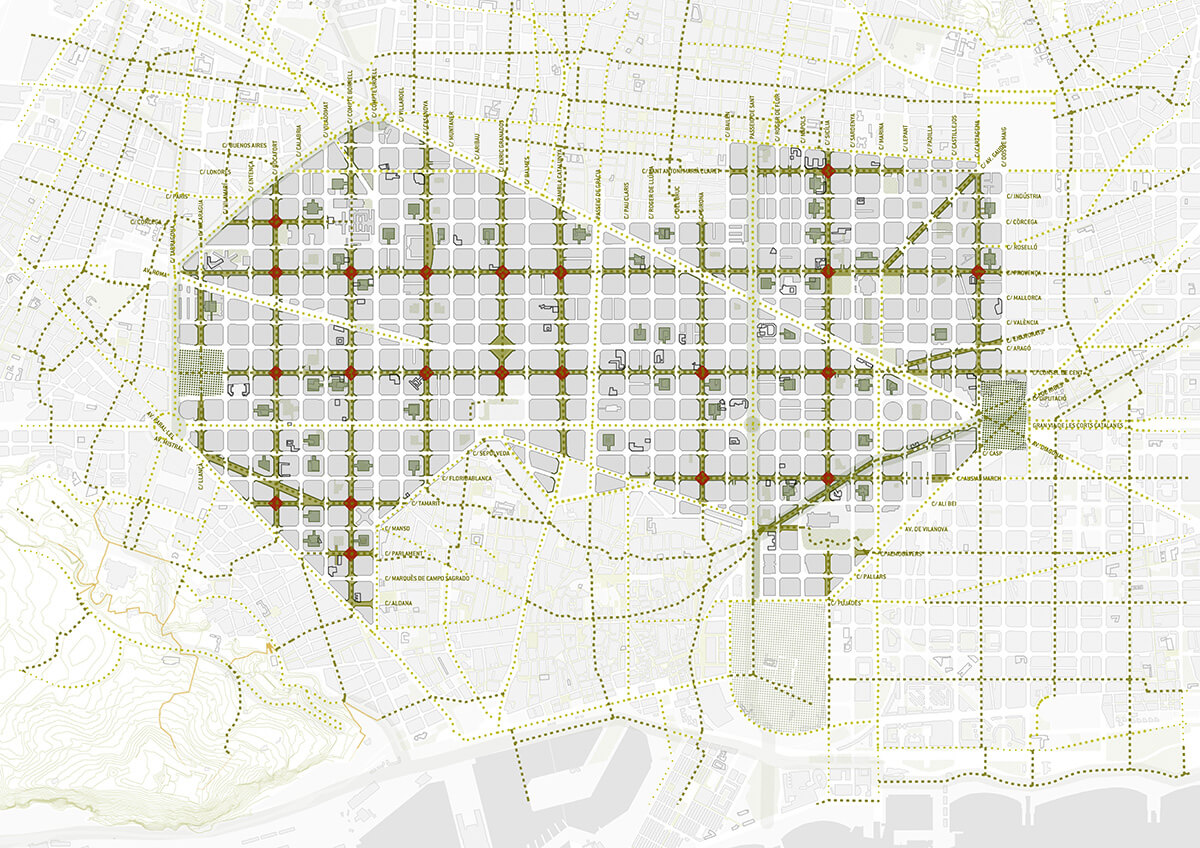

Barcelona and the Green Axes: An Integrated System of Superblocks

Now that the superblock project is entering a new stage, extending throughout the city, it is important to analyze its achievements and future prospects. Podjapolskis (2017), one of the authors critical of the superblocks considers that their extension to the whole Eixample could reduce the diversity of the district and doubts the benefits of establishing only two categories of streets: vehicular and pedestrian. However, this assessment does not seem to take into account the introduction of green axes as an additional typology.

Green Axis between Carrers Almogàvers and Zamora, © Àlex Losada/barcelona.cat, licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

Green axes seem to be precisely the guiding elements of this new stage that generates enormous expectation but also some criticism. Anyone who lived in Barcelona between 2000 and 2015 knows that the street in the Eixample where everyone wanted to move or open a business was Enric Granados. By pedestrianizing the street and increasing vegetation, Granados Street became an oasis in the noisy neighborhood while increasing its vitality.

Although discrepancies have arisen in recent years over the increase in the space occupied by restaurant terraces, the fact is that it continues to be a reference for imagining new green axes. It is difficult to think of better publicity than to show successful results, and here it would be interesting to point out also the most recent remodeling of Cristóbal de Moura Street, a prototype of green axis whose aspirations visibly exceed those of the Enric Granados project.

Green Axis Carrer Cristobal de Moura, © GA Barcelona

It is understandable, however, that the change in scale of the interventions may generate doubts, since it is very different to pacify a single street than one every three. Salvador Rueda himself has been critical of the City Council’s new guidelines, which would seem to move away from the initial premises (Suñé, 2022). It is essential to maintain an integral conception of the city for the future, in which the negative consequences of the plan are also foreseen in order to minimize them without losing the basic objectives.

Network of new green axes and squares, © Ajuntament de Barcelona

Barcelona’s Ecological Transition: Towards a More Participatory and Sustainable City

It is difficult to draw up a complete and objective balance sheet of the interventions carried out so far. In all cases, it is clear that there is room for improvement, whether in terms of communication, marketing, decision making or implementation of concrete designs. That almost half of polled neighbors still show reticence about the superblocks is more likely a consequence of specific functional and design failures or even political animosities, rather than a rejection of the guiding principles of the proposal (El Periódico, 2023).

In all cases, citizen participation is called to play a decisive role in the acceptance and eventual success of the program and is clearly one of the points to work on. Strengthening and systematizing the objective study of the achievements of the superblocks (factors such as noise, air pollution and even interaction between people are perfectly measurable), can help to visualize improvements in their implementation and reconcile dissatisfied neighbors with their new surroundings.

Poblenou Superblock, © Curro Palacios/barcelona.cat, licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

And if Cerdà’s project was to be taken as a model, it should be because of its resilience. The heterodox application of the Eixample grid is what has guaranteed its survival and extended its validity. Urban planning has never been an exact science and the ability to adapt to environments of different functionality, morphology and density will also be key, not only in the consolidation of the project in Barcelona, but also to facilitate its export to other cities. On this initiative it is advisable to review the suggestive study developed by Sven Eggimann (2022). In all cases, the potential of the superblocks is enormous and has not yet reached its full potential. We invite you to join us and follow its evolution in the coming months and years, without ever giving up critical thinking.

Urban furniture within the Sant Antoni Superblock, © RdA Suisse/Flickr, licensed under CC BY 2.0

Text: Pedro Capriata

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Ajuntament de Barcelona (marzo 2021). Resolución de los concursos de ideas de Superilla Barcelona. https://ajuntament.barcelona.cat/superilles/es/content/resolucion-de-los-concursos-de-ideas-de-superilla-barcelona

Centre de Cultura Contemporània de Barcelona (2014). Salvador Rueda.

https://www.cccb.org/es/participantes/ficha/salvador-rueda/6055

Eggimann, S. (2022). The potential of implementing superblocks for multifunctional street use in cities. Nature Sustainability 5, 406–414.

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-022-00855-2

EIT Urban Mobility (2020). How can Superblocks transform public space? | With Salvador Rueda.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=H4xPdbPjmzc&t=2s

El Periódico (enero 2023). Aval a los nuevos radares en Barcelona, gran división sobre las ‘superilles’ – Encuesta preelectoral del GESOP.

https://www.elperiodico.com/es/barcelona/20230131/encuesta-elecciones-municipales-barcelona-2023-radares-superilles-patinetes-82220193

Gehl, J. (2006). La humanización del espacio urbano. Editorial Reverté.

Jacobs, J. (2011). Muerte y vida de las grandes ciudades. Capitán Swing Libros.

Podjapolskis, R. (2017). Supermanzanas bajo sospecha: el proyecto de Superislas para Ensanche frente a su alternativa. Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya.

https://upcommons.upc.edu/handle/2117/108293

Rueda, S. (2017). Ecosystemic urbanism: a way to make cities more sustainable. Barcelona Metròpolis, Num 102,

https://www.barcelona.cat/bcnmetropolis/2007-2017/en/author/salvador-rueda/

Suñé, R. (abril 2022). El ‘padre’ de la supermanzana cuestiona por ineficiente el plan del Ayuntamiento de Barcelona. La Vanguardia.

https://www.lavanguardia.com/local/barcelona/20220429/8233036/padre-supermanzana-cuestiona-ineficiente-plan-ayuntamiento-barcelona.html

Wikipedia (2022). Plan Cerdá

https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Plan_Cerd%C3%A1

Barcelona’s Superblocks and Green Axes, a Pathway Towards a More Sustainable City

The City Accelerates the Process of Urban Regeneration With the Incorporation of Green Axes and Squares.

Sant Antoni Superblock, © Mariona Gil/barcelona.cat, licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

Superblocks: Reinventing Barcelona’s Public Spaces

One of the most stimulating urban proposals of the last decades can be found, once again, in the prolific Barcelona. We are talking about the Superblocks or Superilles, an approach that goes beyond the implications of its name and encompasses a comprehensive renovation project for the city. As expected, the first superblocks implemented have focused the debate on the potential qualities and drawbacks of the concept. Barcelona’s City Council presented them as pilot tests, but also as an inevitable change of model that would ensure the sustainability of the city in the medium and long term. Perhaps this is where the communication problems begin because it is as if we were being told “try this and see if you like it… but if you don’t, you’ll have to eat it anyway”.

But let’s start by defining what superblocks are. In the most elementary sense, they are mega-blocks made up of the union of nine pre-existing blocks. The merger is obviously not achieved by filling the spaces between blocks with buildings, but by transforming the public space between them. Changes include new uses and restriction of car access in favor of pedestrians and bicycles. The objectives include reducing noise, traffic and pollution within these areas, providing citizens with more and better living spaces, and overall, making Barcelona a more sustainable city.

Playground within the Poblenou Superblock, © Curro Palacios/barcelona.cat, licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

While in theory this method would be applicable in any city with a regular layout, it is particularly interesting in the context of the Eixample, the Barcelona expansion project devised by Ildefons Cerdà in the mid-19th century. The Cerdà Plan was not followed to the letter, but the grid layout, the proposed street widths and the characteristic chamfers at the corners of the blocks were almost always respected. These chamfers are what now enable the creation of public squares of different character at the pedestrianized intersections.

Revitalizing the Streets: Salvador Rueda and the Legacy of Jane Jacobs

Let us now try to explore the origin of this concept. The driving force behind this proposal is Salvador Rueda, a psychologist specializing in urban planning and sustainability issues with an extended career in public institutions. While Rueda’s specific approaches are novel, they are based on principles that have been at the center of the urban planning debate for decades and that revolve mainly around the prioritization of pedestrian space.

It would therefore make sense to look for precedents in the ideas of Jane Jacobs, a seminal figure in the emergence and consolidation of current urban theories. Jacobs (2011) put people at the center of her plan, analyzed existing situations and proposed strategies such as functional diversification to improve and revitalize urban environments.

Pavement markings at Carrer Pelai, © Ajuntament de Barcelona, licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

In one of the premises of The Death and Life of Great American Cities, Jacobs recommended reducing the size of city blocks. At first we might think that Rueda is moving in the opposite direction of the author, but if we read Jacobs’ explanation carefully, we will see that this is not the case. The objective of reducing blocks was to increase and diversify pedestrian flows, something that the superblocks achieve, at least in part.

Jacobs’ only objection that might be relevant in this context would be that large blocks make access to public transportation more difficult. But if these were to magically split as her diagrams suggest, it is unlikely that public transport would alter its established routes. It would seem then that the superblocks follow Jacobs’ theoretical framework in most of their guidelines.

Slowing Down Flows and Blurring Boundaries: Jahn Gehl and the “Soft Edges”

In the superblocks we can also glimpse at concepts proposed by the Dane Jan Gehl, another of the great references of contemporary urbanism. Gehl has played a crucial role in the pedestrianization of Copenhagen, but above all he has exerted an enormous influence through his texts. Among his guiding ideas is one that is also central for Rueda: reducing traffic speeds. In the superblock prototypes in Barcelona, not only has car access been restricted, but the speed limits applied might seem excessively rigorous (10 km/h).

Running track within the Poblenou Superblock, © Curro Palacios/barcelona.cat, licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

Another of Gehl’s (2006) premises that we see partially applied are the so called “soft edges”, which may consist of permeable facades with social or commercial activity, or alternatively a succession of in-between spaces that blur the boundaries between public and private. In these cases, vegetation should play a decisive role. It is foreseeable that the conditions of each environment will determine the type of soft edges to be applied and therefore the results may vary.

In the Sant Antoni Superblock we see a more stimulating environment due to the continuity of the facades and the presence of stores. In Poblenou, on the other hand, with discontinuous volumes, the interaction between public and private seems to depend more on in-between spaces. The concept of soft edges is perfectly in tune with the objectives of the superblocks and should perhaps be incorporated more consistently into the debate regarding the future of the urban plan. In what ways could the interaction between buildings and the street be improved?

Sant Antoni Superblock, © Mariona Gil/barcelona.cat, licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

It is timely to recall a final theme that shapes Gehl’s theories: his warning about lengthy paths and oversized spaces. From this perspective, the superblocks perhaps start with a disadvantage: in Cerdà’s Eixample the large dimensions of the grid are a binding framework and indeed in certain cases the pedestrianized areas may seem excessive or underutilized. But precisely for this reason it is essential to be aware that in order to transform public space it is not only necessary to create places for citizens and encourage mixed activities: it is equally important to maintain accurate scales through the fragmentation of paths and spaces.

Barcelona and the Green Axes: An Integrated System of Superblocks

Now that the superblock project is entering a new stage, extending throughout the city, it is important to analyze its achievements and future prospects. Podjapolskis (2017), one of the authors critical of the superblocks considers that their extension to the whole Eixample could reduce the diversity of the district and doubts the benefits of establishing only two categories of streets: vehicular and pedestrian. However, this assessment does not seem to take into account the introduction of green axes as an additional typology.

Green Axis between Carrers Almogàvers and Zamora, © Àlex Losada/barcelona.cat, licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

Green axes seem to be precisely the guiding elements of this new stage that generates enormous expectation but also some criticism. Anyone who lived in Barcelona between 2000 and 2015 knows that the street in the Eixample where everyone wanted to move or open a business was Enric Granados. By pedestrianizing the street and increasing vegetation, Granados Street became an oasis in the noisy neighborhood while increasing its vitality.

Although discrepancies have arisen in recent years over the increase in the space occupied by restaurant terraces, the fact is that it continues to be a reference for imagining new green axes. It is difficult to think of better publicity than to show successful results, and here it would be interesting to point out also the most recent remodeling of Cristóbal de Moura Street, a prototype of green axis whose aspirations visibly exceed those of the Enric Granados project.

Green Axis Carrer Cristobal de Moura, © GA Barcelona

It is understandable, however, that the change in scale of the interventions may generate doubts, since it is very different to pacify a single street than one every three. Salvador Rueda himself has been critical of the City Council’s new guidelines, which would seem to move away from the initial premises (Suñé, 2022). It is essential to maintain an integral conception of the city for the future, in which the negative consequences of the plan are also foreseen in order to minimize them without losing the basic objectives.

Network of new green axes and squares, © Ajuntament de Barcelona

Barcelona’s Ecological Transition: Towards a More Participatory and Sustainable City

It is difficult to draw up a complete and objective balance sheet of the interventions carried out so far. In all cases, it is clear that there is room for improvement, whether in terms of communication, marketing, decision making or implementation of concrete designs. That almost half of polled neighbors still show reticence about the superblocks is more likely a consequence of specific functional and design failures or even political animosities, rather than a rejection of the guiding principles of the proposal (El Periódico, 2023).

In all cases, citizen participation is called to play a decisive role in the acceptance and eventual success of the program and is clearly one of the points to work on. Strengthening and systematizing the objective study of the achievements of the superblocks (factors such as noise, air pollution and even interaction between people are perfectly measurable), can help to visualize improvements in their implementation and reconcile dissatisfied neighbors with their new surroundings.

Poblenou Superblock, © Curro Palacios/barcelona.cat, licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

And if Cerdà’s project was to be taken as a model, it should be because of its resilience. The heterodox application of the Eixample grid is what has guaranteed its survival and extended its validity. Urban planning has never been an exact science and the ability to adapt to environments of different functionality, morphology and density will also be key, not only in the consolidation of the project in Barcelona, but also to facilitate its export to other cities. On this initiative it is advisable to review the suggestive study developed by Sven Eggimann (2022). In all cases, the potential of the superblocks is enormous and has not yet reached its full potential. We invite you to join us and follow its evolution in the coming months and years, without ever giving up critical thinking.

Urban furniture within the Sant Antoni Superblock, © RdA Suisse/Flickr, licensed under CC BY 2.0

Text: Pedro Capriata

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Ajuntament de Barcelona (marzo 2021). Resolución de los concursos de ideas de Superilla Barcelona. https://ajuntament.barcelona.cat/superilles/es/content/resolucion-de-los-concursos-de-ideas-de-superilla-barcelona

Centre de Cultura Contemporània de Barcelona (2014). Salvador Rueda.

https://www.cccb.org/es/participantes/ficha/salvador-rueda/6055

Eggimann, S. (2022). The potential of implementing superblocks for multifunctional street use in cities. Nature Sustainability 5, 406–414.

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-022-00855-2

EIT Urban Mobility (2020). How can Superblocks transform public space? | With Salvador Rueda.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=H4xPdbPjmzc&t=2s

El Periódico (enero 2023). Aval a los nuevos radares en Barcelona, gran división sobre las ‘superilles’ – Encuesta preelectoral del GESOP.

https://www.elperiodico.com/es/barcelona/20230131/encuesta-elecciones-municipales-barcelona-2023-radares-superilles-patinetes-82220193

Gehl, J. (2006). La humanización del espacio urbano. Editorial Reverté.

Jacobs, J. (2011). Muerte y vida de las grandes ciudades. Capitán Swing Libros.

Podjapolskis, R. (2017). Supermanzanas bajo sospecha: el proyecto de Superislas para Ensanche frente a su alternativa. Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya.

https://upcommons.upc.edu/handle/2117/108293

Rueda, S. (2017). Ecosystemic urbanism: a way to make cities more sustainable. Barcelona Metròpolis, Num 102,

https://www.barcelona.cat/bcnmetropolis/2007-2017/en/author/salvador-rueda/

Suñé, R. (abril 2022). El ‘padre’ de la supermanzana cuestiona por ineficiente el plan del Ayuntamiento de Barcelona. La Vanguardia.

https://www.lavanguardia.com/local/barcelona/20220429/8233036/padre-supermanzana-cuestiona-ineficiente-plan-ayuntamiento-barcelona.html

Wikipedia (2022). Plan Cerdá

https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Plan_Cerd%C3%A1